Your 4-Step Roadmap to Writing a Great Book: A Guide for First-Time Authors

what to expect and how to set yourself up for success

Writing a book might sound romantic—until you actually try to do it.

Between the initial idea and the final draft lies a wilderness most writers don’t expect, a maze of decisions, doubts, and unfamiliar territory. Many first-time authors end up confused, overwhelmed, and disappointed—either with the process, the product, or both.

If you’re dreaming about writing a book, or struggling in the thick of it, you might be wondering exactly what that process will look like and what kind of support will help you cross the finish line and get it published.

Whether you end up self-publishing or getting a traditional book deal, there are a lot of steps along the way—and there’s a lot of lingo that can cause confusion. Plus, it ain’t cheap. You know enough to recognize that you can’t just dump some words in a doc, slap on a Canva cover, and send it off to Amazon—at least not if you want to have a book you’re actually proud of, or that anyone will read (besides your mother).

You probably know you’ll need some editing. But what kind? How much? And editing only comes in once you’ve finished that first draft. What if you’re struggling to get that far?

First of all, let’s throw any shame that brings up right out the window. It’s 100% normal to struggle to write a first draft. Only 3% of people who start writing a book actually finish. And even established authors working on their 5th or 10th books hit roadblocks.

That’s why I created this guide to demystify the book creation process, alert you to common pitfalls, and point you in the right direction if and when you’re ready for professional support.

No matter how you slice it, writing a book is hard business. In the 16+ years I’ve been working as a freelance editor, I’ve yet to come across an author who said otherwise. Having the right kind of support at the right time can be the difference between a half-written draft collecting digital dust and a finished book you’re proud to share with the world.

Even if you’re going to finish your book no matter what, professional guidance can bring relative ease and joy to the experience—one that can often feel lonely, frustrating, and incredibly vulnerable. Plus, it can save you valuable time and even money in the long run.

In my 16+ years as a freelance editor, I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve been hired to edit a book that clearly needed significant structural help: chapters out of logical order, big ideas unclear or inconsistent, lots of repetitive or unrelated content, missing support and long-winded personal stories. This author would have benefited from professional help much earlier in the process, but now they’re stuck trying to completely rework a manuscript they’ve already labored over for months or even years. Other times, an author set out to hire a proofreader when what they really needed was a line or developmental editor, only they had no idea what the difference was, so they ended up having to pay for proofreading twice.

I’ve seen similar struggles in my decade teaching upper-level writing classes. My students are used to getting a prompt and diving straight into drafting, the most conscientious among them maaaaaybe making a rudimentary outline first. Then they wonder why the drafting process is so hard—or why their “first draft” is a complete mess. (I use quotation marks there because, for me, “first draft” means a complete draft that represents the writer’s best effort before getting professional editing. The first effort is what I call a rough draft, which requires revision to become a true first draft.) They’re shocked when I tell them we’ll be doing at least four drafts and that we won’t even look at their punctuation until the last round of revisions. Shock turns to disbelief when I explain that, in my class, they’ll be required to submit six steps of pre-writing before the first draft.

In both situations, the confusion comes from a faulty (or absent) understanding of the process—of what it takes to produce truly great writing. Even a short essay of 2-3 pages requires significantly more work than most anticipate in order to reach the level of clarity, concision, and eloquence that makes readers want to keep reading. With a book-length project, it’s even more important to begin with appropriate expectations and follow a proven process. The longer the piece, the more complex the ideas. The more complex the ideas, the easier it is to lose the reader—or lose your focus while writing. Strong writers might be able to take a new idea and pound out a decent blog post in one sitting with much of a “process.” Not so for a book.

The key to actually finishing your book (without losing your mind) and producing one you’re proud of (without wasting thousands of dollars or years of your life) is to set yourself up for success from the beginning.

To do that, you need to

understand the process,

anticipate roadblocks, and

know where to turn if and when you need support.

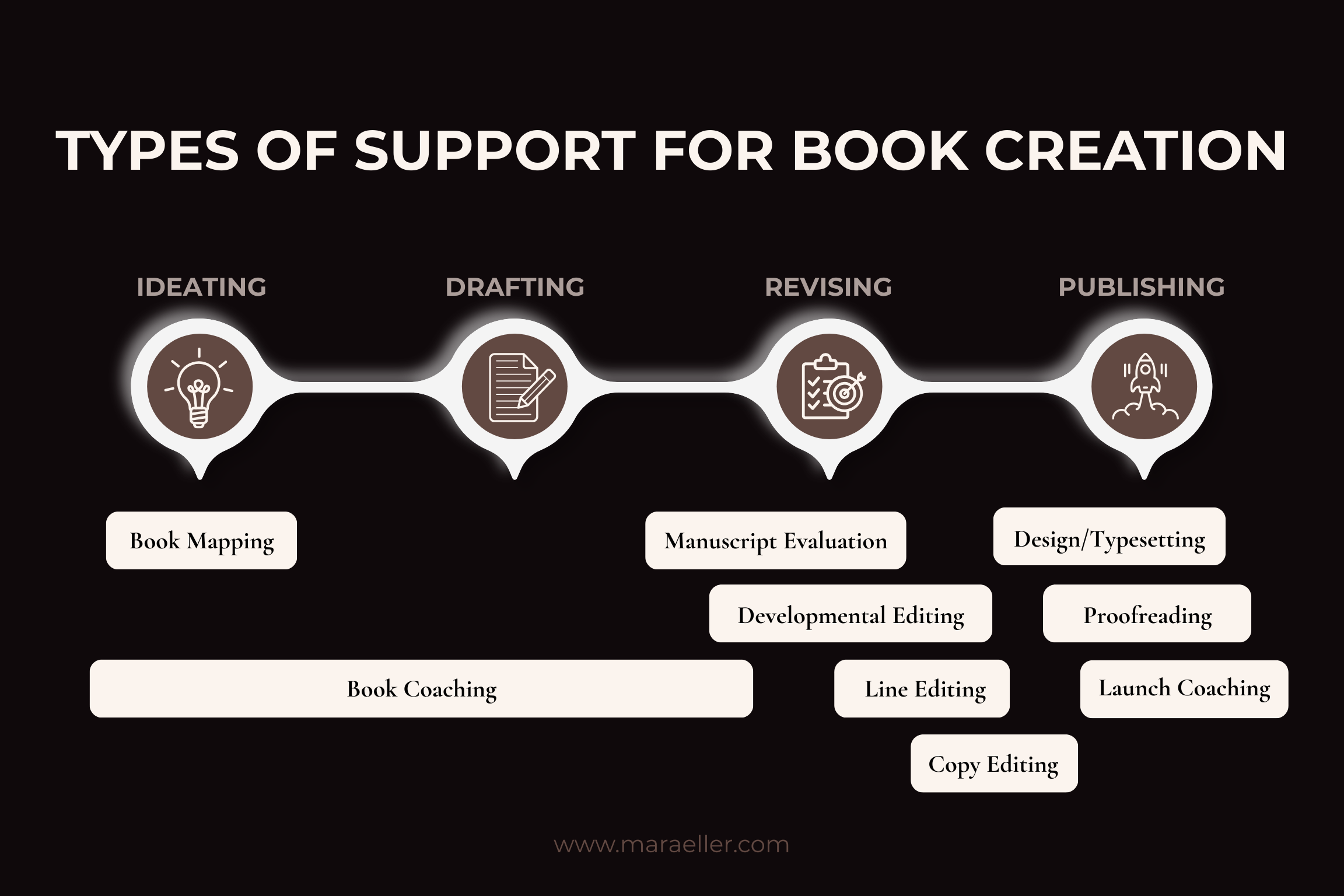

Below, we’ll look at the four phases of book creation that every author must go through to produce a high-quality book as well as the different levels and types of support available during each phase: when they come into play and how they help.

Note: This article is written specifically for nonfiction authors—from prescriptive nonfiction like self-help to creative nonfiction like memoir. That said, the phases outlined below and many of the potential pitfalls remain the same for fiction. Just keep in mind that some of the nuances will be different.

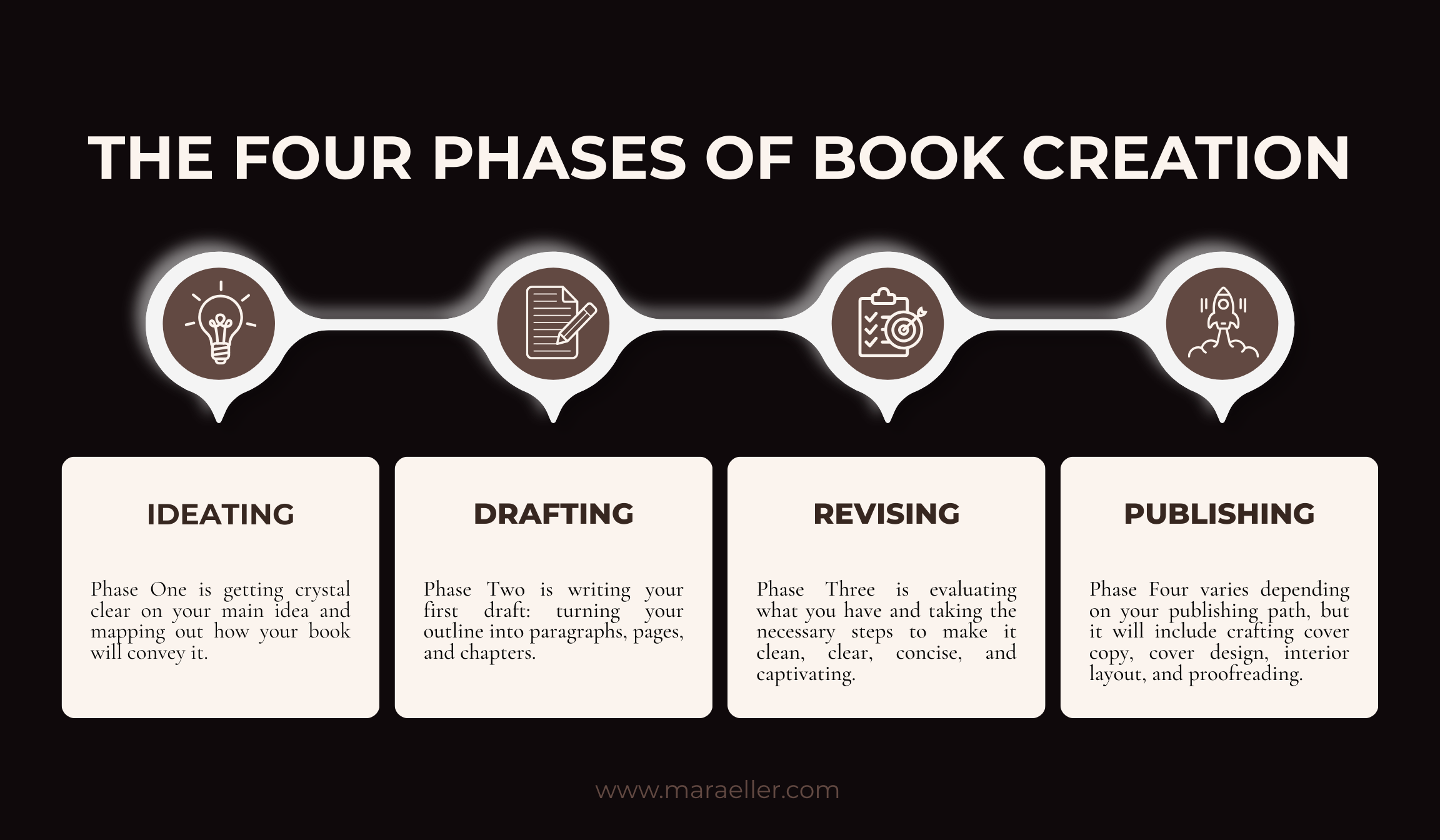

THE FOUR PHASES OF BOOK CREATION

When we hear “write a book,” most of us probably imagine sitting at a computer and typing words into a document. You probably know enough my now to understand that a lot of other stuff also has to happen in order to end up with a book you can hold in your hands, but you’d be far from alone if you still expect that the bulk of your time will be spent putting words onto the page. After all, that’s why it’s called “writing” a book, right?

Wrong.

When it comes to producing a high-quality book, there are four essential phases you’ll need to pass through, dedicating approximately equal time/energy to each:

Ideating

Drafting

Revising

Publishing

Notice that “drafting”—what we usually think of as “writing”—is just one of four steps. The time you spend actually putting words together in your manuscript document will only be one quarter of the total time (and energy) you spend creating your book.

Author Chris Abani said, “People think that writing is writing, but actually, writing is editing. Otherwise, you're just taking notes.” As an editor, I appreciate his sentiment, but I have to expand that to say that writing is thinking + editing. And if you want to publish (and have people buy/read it), that’s another major part of the process.

The truth is that great writing is so much more than writing. And great writers recognize that fact.

Please note that the divisions between these phases are not as clear as the graphic implies. You might find that you need to do a bunch of freewriting during the Ideating phase before you can figure out what you really want to say. Or, when you’re halfway into your rough draft, you might find you need to adjust your outline. Or maybe you find you need to re-write an entire chapter when you’re technically in the Revising phase. And you should always think about your publication goals during the Ideating phase since you have to know who your book is for in order to craft your book’s argument.

Give yourself permission to move fluidly between the four stages—doing whatever is necessary to create the best book possible. Only don’t think you can skip or rush through one of the phases. Each is essential, and an astute reader can tell when one has been neglected.

PHASE ONE: IDEATING

A book always starts with an idea. Before you start writing, you need a plan: a clear map of what you want to say and how you’ll say it. This requires that you answer the following questions:

What is my book about?

Who is it for?

What problem does it solve?

What makes it unique?

What is the central argument or takeaway?

What are the steps of the journey from the first page to the last?

Key here is knowing how much clarity—and how much detail—is enough.

Some writers think simply knowing their topic is enough. This is a big mistake that leads to months if not years of “wandering in the wilderness,” writing in circles as they try to figure out what they really want to say, sometimes becoming more confused rather than less as the words pile up.

Others want to have every detail planned, down to the topic of every single paragraph and every piece of supporting evidence—or in the case of memoir, every single scene. They are convinced that they can create a perfect outline, and that when they do, the writing will be effortless. It can also become an excuse to avoid the vulnerable task of actually writing.

The sweet spot is when you have a crystal clear main idea for the book as well as a good sense of the argument for each chapter and a bullet-style list of the ideas, examples, and anecdotes you’ll include in each one. To get there, you’ll need a thorough understanding of who you’re writing for, what problem you’re solving for them, and what the steps are to get them there. For memoir, the reader’s journey follows yours, so you’ll need to know the overarching theme, the before and after for the main character (you), and the primary complications you navigated to get there, broken down into parts and chapters.

Crucial to this phase is providing yourself with a clear guiding structure for moving through your argument or story and breaking the book down into manageable chunks, i.e. chapters. This will help you avoid overwhelm and keep you on track when rabbit trails beckon.

This phase lays the foundation for your book. The clearer your main idea and structure are, the better your book will be. Conversely, if your foundation is shaky—if your ideas are half-baked and poorly organized—the best writing in the world can’t save it.

I want to touch on a common struggle or misconception here. While I do always recommend creating a detailed outline before writing your first draft, that does NOT mean you can’t write as part of your Ideating phase. I’ve found over and over that there are some writers who simply cannot make an outline before they write out their ideas, and still others can make an outline if forced to do so but cannot execute that outline. They simply must write out their ideas in sentences and paragraphs first. That’s how they discover what they really think.

If that’s you, I’m here to tell you: that is 100% ok! Freewriting—writing out your ideas as they come without editing—is actually a wonderful tool during the Ideation phase. Just don’t mistake that writing for a first draft. If you need to write for a while and then look through what you’ve written to discover the big ideas you’ll use for your outline, go for it! But you do need an outline/book map before you’re ready to officially work on that first draft. Think of your freewrite material like blog posts or journal entries that an author might use as inspiration for a book. They might even pull some material directly, but they would never paste them in a row and call it a book.

No two authors will follow exactly the same steps in exactly the same order for the Ideating phase. The same author won’t follow exactly the same steps from one book to the next! What matters is that you do what works for you to produce that detailed book map that will guide every step that follows.

A book can only be as good as its ideas, which is why this step is so important—and why I strongly encourage first-time authors to seek professional help in the Ideating phase rather than waiting until after they’ve written the first draft. The two forms of professional support most commonly available for the Ideating phase are Book Mapping and Book Coaching.

Support: Book Mapping

The goal of the Ideating phase is creating a detailed outline or book map: a clear plan for what your finished book will look like and how you’ll get there. According to book map gurus Ariel Curry and Liz Morrow, “A book map is a visual representation of your book’s structure. It can be as high-level or as detailed as you want, but the goal is that it provides a clear picture of exactly what content is going to go where in your book—creating a ‘map’ that you can follow as you’re writing.”

Liz and Ariel’s book Hungry Authors is a great resource if you want to do this step on your own, but I highly recommend getting some professional insight. Why? Because a book is only as good as its structure. And because having a clear, well-thought-out book map dramatically increases your chances of actually finishing that first draft.

Most authors I work with on this step have realized that it’s extremely hard to get perspective on their own ideas—especially since they’ve probably been thinking about them for years if not decades. For example, many life or business coaches decide they want to write a book so they can share their methods with more people. But when they start trying to write down everything they’ve done with clients over the last 15 years, it quickly gets overwhelming and chaotic. Coaching is rarely linear, but a book, by definition, is. What order is best? What are the bigger “steps” in their coaching process that involves dozens if not hundreds of exercises? This can be incredibly challenging, not to mention time consuming.

Memoirists also struggle mightily with this step. On the surface, it can seem simple: obviously, you start at the beginning and tell the story in chronological order. But what exactly is the beginning? And what is the narrative arc? What should be included, and what should be left out? The possibilities are virtually infinite, since any detail from the author’s life could become material. And then there’s the question of genre. Will it be pure memoir or some kind of hybrid, incorporating reflection questions or educational content?

Of course, before you can make a map, you have to know what the main idea of your book is. What is your central argument, message, or theme? What is the overarching transformation for your reader and/or for you, in the case of memoir?

These are complex questions, the answers to which will direct everything that follows. That’s why it pays off to invest in professional guidance at this stage of the journey. Getting help nailing down your main idea and how best to structure its delivery can save you valuable time (and hair pulling), set you up for an easier time drafting, and ensure that your draft doesn’t require massive edits in the revision stage.

Book Mapping is sometimes offered as a stand-alone service with a fixed price, or it may be part of a larger package offered by a book coach, which is what I do. You can find it offered in a group or course, but that will still leave you doing the bulk of the “figuring out” on your own. If you can swing it, most authors find it well worth it to invest in one-on-one help at this stage.

I’ll add that, when done well, a book map will provide you with the bulk of the language you need for a standard book proposal—the “book resume” that you will submit to agents and publishing houses if you’re looking for a traditional book deal.

For prescriptive nonfiction (not memoir), standard practice is to require a book proposal with several sample chapters, but they do not the expect the entire book to be written before it is accepted. (Memoirs, which read more like fiction, do need a completed manuscript in order to be pitched.) However, I’ve worked with several authors who chose to write the entire book first anyway because they knew that the writing and revising process might significantly alter their book idea. Plus, they wanted to retain creative control over those steps and preferred to pitch a more finished product.

Whether you’re planning to self-publish or pitch traditional publishers, it’s extremely helpful to come up with most of the material that goes into a book proposal before you start drafting. Hence, the book map. Or, if you want a bit more guidance, a book coach.

Support: Book Coaching

“Book coach” is a bit of a catch-all term for someone who helps you bring your book into the world. It can basically encompass anything you need help with, but book coaching most often refers to providing professional guidance during the Ideating phase. This will typically include book mapping but can also extend beyond it.

Once an author has a strong book map (and/or a book proposal), a book coach can help create a schedule for the drafting process with deadlines and accountability. This might include providing feedback on the first few chapters as they are written (that’s what I typically do) to make sure the writer has a good idea of how to execute the book map.

It’s one thing to have an outline of what you’re supposed to write. It’s another to actually turn those bullet points into the flowing prose you’ve been imagining. That’s why my Momentum Book Coaching package spans the Ideating and Drafting phases, ensuring that you not only know what you’re supposed to write but how to write it effectively.

Book Coaching varies widely in terms of how it’s offered and priced. Some coaches offer a coaching package with a fixed price—that’s what I do. Each client receives customized guidance within that package, depending on their needs. Other coaches charge by the hour (usually upwards of $100/hour for experienced coaches).

Anyone worth their salt will offer a free consultation call so you can both see if it’s a good fit—something you absolutely want to do since you’ll be working closely with this person for several months. You’ll want to evaluate their experience and credentials (which you should be able to do on their website), but you also want to get a sense of their style and personality. Some coaches will be more assertive or aggressive, providing strict deadlines and using rigid formulas. Others will be more relaxed and encouraging, providing guidance when you ask but letting you run the show.

The right coach for you will be someone with experience in your genre (remember, memoir is very different from other kinds of nonfiction), a solid track record providing the kind of support you’re looking for (check out their testimonials), and a demeanor that feels both motivating and comfortable. Writing is an inherently vulnerable process, and if you don’t feel safe, you will struggle to make meaningful progress.

If you want to learn more about what it might look like to get my support for this phase, book a free consultation with me by clicking here, and we’ll make a customized, 3-part plan for your progress. Plus, I’ll provide initial feedback on your book idea or existing book map so you walk away with actionable next steps—whether or not we end up working together.

PHASE TWO: DRAFTING

Once you’ve laid a strong foundation with a detailed book map and clear overview of your big idea, it’s time to start drafting. This phase needs less explanation because it’s what we think of when we hear “write a book.”

My clients encounter two primary challenges in this phase:

Resistance raises its ugly head. They find all kinds of creative reasons to do something other than write, and their inner critic goes into overdrive. They feel miserable and progress stalls.

Their outline doesn’t seem to be working. Maybe they find themselves veering way off track, or maybe they follow the outline religiously but it feels awkward and uninspired. They start to question the book map and waste valuable time wondering if they should change direction.

Conquering resistance requires a steady stream of encouragement and is usually supported with clear deadlines and external accountability, such as that provided by a book coach. Regardless, if you find yourself questioning each line you type, try to write without editing. Pretend your “delete” key is broken and/or that if you stop typing for more than a few seconds your progress will be lost. Just get your ideas down and worry about perfecting the prose later.

The second challenge is more complicated. As with the pitfalls of the Ideating phase, the writer must avoid both extremes. It won’t help to throw out your book map and dump 50k words into a document. (Remember that some writers, especially memoirists, find they have to let all the words out onto the page first and then create a their outline. If that’s you, great! That’s totally fine. But that freewriting/braindump process is part of the Ideating phase and must be followed by clarification and organization.)

It also won’t serve you in the long run to force yourself to adhere to an outline that your ideas have outgrown. An important part of the process of writing is discovery. The process of putting our thoughts into sentences and paragraphs brings additional clarity, and if you’re doing it right, your ideas WILL evolve and mature. Remember that your book map is a tool, not a god. If you need to adjust it, go for it! But make sure you have a good reason for doing so.

That’s where having the perspective of a book coach can be extremely helpful. When you’re in the thick of drafting, it can be incredibly hard to distinguish between the disruptive whispers of imposter syndrome or procrastination and the constructive insights of a deepening understanding of your subject. Having someone to bounce ideas off of who knows your book and the market intimately can quickly get you back on track—or help you re-tool your book map to take into account your new idea.

Support: Book Coaching

If you work with a coach during the Drafting phase, they will likely provide emotional support in addition to industry expertise. They can help you overcome internal resistance, keep you on track if you’re tempted to deviate from your book map, or discern whether it might be time to revise the book map in light of new insight you’ve uncovered. They will usually provide external accountability in the form of deadlines, keeping you moving forward towards that completed manuscript.

Unless you truly want a cheerleader—and are willing to pay for it—I’d encourage you to talk to your prospective coach about what kind of support they typically provide during the Drafting stage. I’ve heard of some coaches who seemed to do little more than check in with clients and tell them some version of “You can do it! Keep going!” While having someone in your corner can be powerful (especially if you don’t have anyone in your life who “gets” writing or supports your dreams), you should consider how much you’re willing to pay for it. Finding another writer to cheer you on would be far more cost-effective (and then you can save that money for a great editor!).

In my book coaching package, I leverage my background in editing to provide constructive feedback on the writing itself as clients are working through their first chapters. This helps writers settle into their unique voice, nip bad habits in the bud (before they become embedded in the entire book), and employ strategies to make their process smoother and faster.

One writer I’ve been working with decided he wanted to write the entire book with my guidance, benefitting from my feedback and instruction every step of the way. He’ll end up with a manuscript that can skip straight over developmental editing (and probably line editing too) because he’s getting that chapter by chapter.

Many writers hesitate to invest in professional help at this stage because they feel like they should be able to do it on their own. After all, no one can make you put your butt in the chair but you, right?

While that’s true, it’s also a lot more complicated than that. By that logic, you might say that all it takes to run a marathon is lacing your shoes and pounding the pavement, but you probably wouldn’t expect to get a good time on your first marathon (and avoid injury!) without paying for a coach. Drafting a 50-65,000-word manuscript is definitely a marathon—it actually takes most people more time to finish a (high-quality) book than to train for a marathon. So kick that “should” to the curb and treat this endeavor like the marathon it is by investing in the support you need.

PHASE THREE: REVISING

Once you’ve got a full rough draft, you’re ready to revise.

Start by reading your draft yourself and looking for any holes or glaring issues. If you wrote your introduction first, you’ll almost certainly need to significantly revise it to match the more mature encapsulation of your main idea in your conclusion. I also recommend looking back at your book map and comparing it to your actual draft. Does it match? Has it changed? Do you like the new organization?

Especially if you’re not working with a book coach, I highly recommend you work through a revision process on your own before hiring an editor. This will potentially save you money in the long run because your manuscript will require fewer passes, and it will also enable the editor to address more nuanced concerns because you’ll have taken care of the obvious ones already. And if you can cut some non-essential material or condense some wordy passages, that will lower your word count and further reduce your editing cost.

Revision can require anywhere from 3-10 passes (or more!), but it can be divided into two major categories: what you’re saying and how you’re saying it.

What: This layer focuses on what you’re saying, your content, at the global and chapter level. Is the main idea clear and consistent throughout? Do all the chapters clearly support that main idea? Are any steps missing for the reader’s journey? Does the content of each chapter clearly support the main idea of that chapter? Do any chapters need more support?

How: Once you’re super solid on what you’re saying, you can shift to focusing on how you’re saying it. You want to revise for clarity, consistency, and concision. How could you communicate the same idea more clearly and in fewer words? Is your style and tone consistent throughout? Are you choosing the most precise and evocative words to convey your ideas?

AJ Harper’s Write a Must Read offers an excellent framework for self-editing, focusing on prescriptive nonfiction (self-help, thought leadership, etc.). For anything slightly more academic, my favorite is The Nuts and Bolts of College Writing by Michael Harvey. Don’t let the title fool you—it’s not just for college students! Hungry Authors by Liz Morrow and Ariel Curry includes some great tips for self-editing (as well as an excellent overview of the book mapping process) for both prescriptive nonfiction and creative nonfiction including memoir. You should also check out my free download From Good to Great: Ten Tips to Write Like a Pro to help you increase clarity and catch some of the most common errors I see as an editor.

At the very least, you should plan to read through your manuscript evaluate whether your main idea is clearly and consistently articulated from beginning to end and see if there’s anything that strikes you as needing some work. Don’t worry too much about punctuation and such at this point; focus on the ideas, support (examples and stories), and organization.

While you can and should do some of this on your own, I always, always recommend seeking professional feedback: hiring an editor. No one can edit their own work well. We’re just too close to it to be able to see it accurately. That’s why even the best, most experienced writers hire editors. Even professional editors hire editors!

Ok, so you know you need to hire an editor. But what kind? That’s the first thing an editor will ask if you contact them for “editing.” What kind of feedback you receive as well as how much it costs will change depending on what kind of editing you request.

The industry does first-time authors no favors by using a bewildering array of terms with little consistency. It would be great if we could just standardize the names for different kinds of editing, but what follows will at least explain the most commonly used names and terms.

The first thing you should know is that “acquisitions editors” are a different thing. They work at a publishing company and focus on finding and acquiring new books/authors. They might offer some limited feedback once you’ve signed with them, but this is not what we think of as an “editor.”

When it comes to professionals who help you improve your manuscript, they are most commonly divided into three groups or types based on the kind of feedback they provide: developmental editing, line editing, and copy editing. (Note: the same person could do more than one kind of editing, and again, the industry is rife with variations of this terminology.)

You can think of these as layers, moving from most abstract/global to most technical/detail-oriented. They must be completed in this order: first the ideas and content (developmental); then the language (line); then the mechanics and details (copy).

I recommend you go through all three layers of edits. Many publishing houses these days will skip the developmental edit (sometimes called a content edit), but in my experience, this results in a sub-standard book. That’s why a lot of authors I work choose to hire a developmental editor on their own even if they’re pitching traditional publishers: they want to make sure their book is really strong before releasing creative control.

Most editors charge by the word, and rates vary depending on the genre and type of editing. You can get a sense of median rates here. In general, editing tends to be the kind of thing where you pay for what you get—in other words, more experienced and sought-after editors will usually charge more. So beware of picking an editor for their low rate. My rates are on the higher end, for example, but I provide extremely detailed feedback with clear explanations based on over 16 years of experience. Plus, I welcome questions and typically meet via Zoom with the author after they’ve reviewed my edits to clarify and brainstorm, and I review their changes when they’re finished revising to make sure everything looks good.

When you’re selecting an editor, be sure to look for signs of their experience: certifications or training, testimonials, titles they’ve edited, and familiarity with the industry. Make sure they have experience with your genre—editorial needs for a prescriptive life-coaching book is very different from those of memoir or even thought leadership.

It’s also a good idea to get a sense of the editor’s style. Some are more technical and formulaic, for lack of a better word. Others are more soulful and creative. A good editor will always work to enhance your style, rather than change it, but even so, no two editors will give exactly the same feedback. Read their website, particularly their own writing, such as on a blog, to get a sense of their personal style. If it’s way off for you, that’s not necessarily a deal breaker (unless it’s straight-up bad writing), but it’s something to keep in mind. You might want to read the preview pages on Amazon of a few books they’ve edited to see what you think of that writing and whether the style is similar to what you saw on the blog.

Finally, you can request a sample edit of a short piece of your writing to get a sense of the kind of feedback you might get. This works well for line and copy editing, but this can be tricky for developmental edits since those can’t really be done on a short sample of a larger work (read on for clarification about the different types of editing). To evaluate a developmental editor, I’d recommend telling them about your book on a Zoom call after sharing your table of contents and maybe the first chapter or two. A great developmental editor will be able to give some feedback about your structure and concept based only on that.

Below is a bit more about each layer of editing: what each stage focuses on and what kind of feedback to expect.

Support: Developmental Editing

“the ideas edit” — focused on ensuring clarity and cohesion at the global and chapter level

Developmental edits are the first line of defense against a mediocre book. This layer considers the manuscript from a bird’s eye view, evaluating what’s on the page to see if it communicates a consistent message clearly and persuasively. For memoir, they consider the narrative arc and the author’s transformation. They provide feedback about what should be cut, where you still need to add content, if and how you should re-organize, and whether your style is working in support of your message.

This stage focuses on your ideas: their clarity, organization, and development. If you did strong work during the Ideation phase, the developmental edit will confirm that you executed your plan and offer a few adjustments and improvements. In this case, you will only need one developmental pass, and the editor will be able to provide some slightly more detailed feedback in addition to the global suggestions. On the other end of the spectrum, if the ideas are not yet solid, they could recommend a complete restructuring or going back to the Ideation phase to clarify the book’s scope and purpose. In that case, you’d need at least one more pass of developmental edits before you’re ready to move on.

For authors who haven’t worked with a professional on the Ideation phase, I usually recommend a Manuscript Review, also called a Developmental Review. This is a slightly more affordable way to get professional feedback on the entire manuscript: strengths, areas for improvement, and recommendations for the path to publishing. This functions like a developmental edit, but it’s less detailed. If a developmental edit looks at the manuscript from a 20,000-foot view, the manuscript review looks from a 30,000-foot view. Depending on the state of the manuscript, the review might recommend a full developmental edit as your next step. Or, if the recommended revisions aren’t too extensive, and you’re able to complete them effectively on your own, you might able to move straight to a “heavy” line edit (one that still addresses a few remaining developmental concerns).

When I perform a developmental edit or manuscript review, the bulk of my feedback comes in a 10-20-page editorial letter. In it, I share my overall impressions and recommendations, including feedback about the overarching message or theme, thoughts on the book’s structure, and chapter-by-chapter suggestions about what to cut, add, move, or otherwise change. I also provide comments about what the author is doing well. The manuscript itself will contain some comments to show where and how the author could implement my feedback, but those will be more limited compared to the other forms of editing.

As I mentioned above, this stage is extremely important. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve received a manuscript for “line edits” only to discover it really needs developmental work first. If that work gets skipped, for whatever reason, you end up with prose that sounds good but, upon closer consideration, doesn’t make a lot of sense. Arguments have gaping holes. Chapter promises are never delivered. Stories seem unrelated to chapter topics. Sentence logic is convoluted. Readers might not be able to name it, but they’ll sense it—and they’ll move on to another book.

If there’s any way you can swing it, do yourself a favor and invest in a (great) developmental editor. This stage is the most subjective, so the quality and stylistic preferences of your editor will have a big impact.

Support: Line Editing

“the language edit” — focused on ensuring eloquence and concision at the paragraph and sentence level

Once the ideas are clear and all the content is on the page and in approximately the right place, you’re ready for a line edit. As the name suggests, this stage looks at your manuscript line by line, ensuring that each sentence is pulling its weight and moving your argument (or theme) forward as powerfully as possible.

The line editor works to ensure your writing is concise, engaging, and consistent. They’ll help you replace weak verbs with stronger ones, vague nouns with precise ones, and dull openers with enticing ones. They’ll eliminate repetitive or confusing sentence structures and make sure each paragraph is cohesive. They’ll also consider organization and flow, only this time between paragraphs and sentences rather than on the global level.

This feedback typically comes in the form of extensive edits in the manuscript itself using “track changes” (Word) or “suggestions” (Google Docs) as well as comments. You’ll be able to see every change the editor made in red (or green) text so you can choose to accept or reject each one. You’ll also want to read through their comments, which will explain the reasons for their changes, pose a question, or suggest a larger revision.

It’s not uncommon for this stage to incorporate a few developmental comments too, addressing anything that still needs a little more help after the developmental edit. If the writing is particularly eloquent and concise already, I’ll usually throw in some copy edits as I go since I don’t have as much to do in the way of line edits. Basically, I try to move the manuscript as far forward along the path to publication as possible in each pass.

Here’s an important truth to remember about editing: there’s only so much an editor can fix in one pass. If a manuscript is riddled with developmental issues that require significant additions and re-writes, there’s no way they can complete a full line edit. I used to explain it to my students like this: if you turn in a C-level essay, I’ll help you get it up to a B. But if you want to get it up to an A, you’ll need another round of edits. On the other hand, if your first draft is a B, one round can get you to that A.

It’s a lot like when we used to Airbnb our home a few times a year to make ends meet, and I had to clean it pretty extensively (we had/have three young kids, so the mess was real). I’d start by picking up the obvious messes, clearing all the surfaces, moving some of our personal stuff into the lockable walk-in closet. Only then would I see the next layer of mess: the little clutter collections I’d become blind to, the crayons hiding halfway under the couch, the dust coating the top of the piano. Even after I addressed those things, I’d always find I had another few hours of work to do before the house was truly ready. While I had a general idea, I couldn’t have known beforehand exactly what would be needed in those final passes; I had to work in layers, letting each one reveal the needs of the next. Editing is similar.

It’s also worth noting that editing is not always perfectly linear. Sometimes cleaning up the wording during the line edit reveals, for example, that a section that seemed like a new idea is actually a repeat of a previous one and can be cut. Or maybe, alternately, an idea needs a bit more explanation for clarity. A great editor will always provide feedback on what the manuscript needs, regardless of the level of editing they’re hired to do (but it can sometimes necessitate negotiating an additional fee).

For example, I recently contracted to perform a line edit, skipping the developmental edit because the author had a very clear idea of the book’s message and audience plus a strong table of contents and a manuscript he’d already revised several times. However, once I got several chapters in, I realized the arguments at the chapter and paragraph level still needed significant developmental work. I provided this level of feedback on the first few chapters and then reached out to the client to share my updated recommendation. I provided the manuscript with my edits to date for his review so he could get a sense of what I was noticing and decide if he wanted to move forward with a hefty dose of developmental edits thrown in with the line edits (a combo sometimes called a “heavy line edit”) for an additional fee. (He did.)

Depending on the state of the manuscript, line edits can end up being the most extensive in terms of the number of corrections and comments, with several or even dozens per page. It’s important to give yourself time and mental space to read through the feedback and digest it before working methodically through the edits—reaching out with any questions that arise.

Support: Copy Editing

“the details edit” — focused on ensuring correctness and consistency in terms of mechanics and formatting

Copy editing is the final step before the manuscript is sent off to be formatted for printing.

Copy editors are focused on making sure your writing is correct—eliminating errors and ensuring it conforms to the conventions of the chosen style guide (Chicago, APA, MLA, etc.). They are concerned with the mechanics of your writing: punctuation, grammar (subject-verb agreement, tense shifts), spelling (commonly confused words, British vs American spellings), and capitalization (Biblical/biblical, President/president). They’ll also standardize formatting and citations. And they’ll usually fix any obvious line-editing issues that slipped through the cracks.

Before handing over your manuscript to a copy editor, you should be sure to discuss which style guide they will be following. (Each traditional publishing imprint will have their own preference, so this primarily applies to authors planning to self-publish.) The most common style guide for the majority of prescriptive nonfiction books is Chicago style, so that’s a good default if you’re not sure. Ultimately, what really matters when it comes to stylistic concerns is that your manuscript ends up being internally consistent, meaning that things are done the same way every time within your book.

This work is extremely detailed. A great copy editor will work through your manuscript in several passes, focusing on different concerns each time. While tools like Grammarly can help, and while that friend who got As in English can too, don’t mistake their work for that of a professional copy editor. There are SO many things to consider, and these details can make the difference between a book that feels a bit sloppy and one that feels truly polished.

While I got my start doing copy editing, I rarely do it anymore, leaving that to the truly detail-oriented experts. The level of knowledge about style guides and the conventions of modern English it requires can become a little tedious for a creative type like myself.

Besides, I always recommend my clients hire a fresh pair of eyes to do this (nearly) final pass. Once I’ve spent a lot of time with a manuscript, I start to know what it says, and like the author, I can easily miss small errors. Hiring a new copy editor is a great way to get a fresh perspective—and a cleaner final manuscript.

I will offer one word of warning here, however: I’ve worked with a few authors on developmental and line edits who then sent the book over to a copy editor who undid some of the work I’d done in the previous pass. This was obviously extremely frustrating. (They won’t be receiving any referrals, that’s for sure!) This is why it’s important that the copy editor use “track changes” so that you can see their work—and reject it if necessary. If you notice that the copy editor seems to be changing things from the way your previous editor had them, consider reaching out to that line editor to get their opinion. Same thing if the edits just strike you as odd.

Remember, it’s your name on the book in the end, so you have the right to evaluate any changes to it. By interviewing your editors before you hire them, you can get a sense of whether they’re open to questions and a more collaborative relationship. It’s not their job to spend hours explaining every edit, but they should be willing to provide their rationale for a few targeted questions.

You might be wondering, “But isn’t there a right and a wrong? Are you saying my copy editor might create errors??” Unless they’re truly terrible, no, a copy editor won’t create errors. However, there’s a LOT that comes down to stylistic preferences. Sure, there are some hard and fast rules like their/there/they’re and ending a sentence with a period. But once you get into the nuances, it gets extremely complex. Are we using the serial/Oxford comma? Are we ok with comma splices, or do we want to ruthlessly eliminate them? Are we using semicolons, or are they a bit too formal? Are we writing out numbers ten and under? Twelve and under? One hundred and under? Are we putting a period at the end of each item on a bulleted list or not? These are all stylistic choices your copy editor will make, some based on the chosen style guide, others not.

That’s why it’s important to stay involved in this part of the process and to evaluate the edits you receive. You probably don’t care whether it’s “twelve” or “12,” but there might be other things that you do care about. The copy edit is your last chance to make any significant changes to the manuscript (without major hassle and extra cost), so it’s wise to stay engaged and ask questions as needed.

One last note on editing: some editors (and publishers) will combine line and copy edits into one pass. This can work well for manuscripts in which the writing is already quite clean and eloquent. In that case, the editor will address the relatively rare instances where sentence structure and word choice could be improved but focus primarily on copy editing concerns. But if the writing is in need of serious TLC in terms of concision, flow, readability, and style, it’s virtually impossible to do all of that plus copy edits in one pass. You’ll always end up with a better final product if you move through each layer of editing individually.

PHASE FOUR: PUBLISHING

After revising to create a clean, cohesive, compelling manuscript, you’re ready to focus on everything required for publication. What this phase looks like really depends on whether you’re traditionally or self-publishing—or going a hybrid route. If you have a traditional book deal, you’ll be working closely with your publishing house at this point, and they’ll be doing the major lifting. If you’re self-publishing, you’ll have a lot more decisions to make.

This phase involves cover design, crafting marketing copy, and all the technical aspects of positioning a book for the market, plus all the promotional activities required to get the word out in today’s saturated marketplace. It’s a lot, and it requires a very different skill set—one that most authors aren’t so excited to develop.

You can find all kind of coaches to help you with this phase, from those focused on building an author platform to book proposal experts and book launch coaches. (A book “launch” refers to all the promotional work that goes into spreading the work and building excitement about your book’s release, basically getting people to buy and read it, and then hopefully tell their friends. Joining another author’s launch team is a great way to get a sense of how it’s done.) And, if you’re self-publishing, I highly recommend you invest in design professionals such as typesetters and cover designers.

Note: Especially when it comes to publishing and marketing your book, there are a lot of scams out there that make “bestseller” promises they rarely deliver on. Do you research, and beware of anything that seems too good to be true—it probably is.

In this article, I’m focusing on what goes into crafting the words inside your book, but if you want to learn more about everything that happens after that, here are a few great resources:

Mikaela Mathews, Self-Publishing Coach – offers comprehensive self-publishing support for first-time authors, helping them hit Amazon bestseller lists (this one is definitely not a scam!)

Ariel Curry, Acquisitions Editor and Former Book Coach (and my personal mentor!): comb through her Substack archive for some excellent articles, such as this one on book proposals

Hungry Authors Podcast: dozens of super practical episodes, such as this one on navigating the publishing industry with Jane Friedman (see below)

Before and After the Book Deal by Courtney Maum: tons of free content on traditional publishing and book marketing

Jane Friedman, Industry Expert: perhaps the most comprehensive and reputable blog out there, with sections on self-publishing, author platform, book marketing, and much more

Bookmark those resources for later, but in terms of getting the words inside the book ready for publication, that comes down to proofreading.

Support: Proofreading

After the copy edit, the manuscript will go to a designer to format it for the size of your book, finalizing it into a print-ready PDF. This usually involves hyphenating long words so that the lines are relatively equal in length, as well as adding page numbers, pull-quotes (if you’re doing those), and any special formatting.

Once it’s all set, the PDF goes to a proofreader for a final review. Their job is to catch any errors created by the design process (like strange hyphenation), as well as anything that snuck through the copy edit. As my editor friend Ariel Curry puts it, “the goal is to catch every possible mistake before the text is immortalized in the printed [or digital] pages of a book.”

Some people conflate copy editing and proofreading, but they are really two different things. The proofread is exactly that: a final readthrough of the “proofs” for the book. No significant changes should be made at this stage, as altering the number of characters on a line can change the line-breaks and create new problems. Some designers will charge extra if you request anything major. That’s why you need a copy edit first, and then a final proofread.

If there’s any stage of the editing process you could do yourself, this is probably it. Errors should be very few and quite subtle, so if you miss some, it’s not a huge deal. Beta readers (especially the ones who aced English) can also be helpful at this stage. Just keep in mind that it’s far too late to make any changes to the content.

After the final proofread and final touches to the cover, it’s off to the printer! Of course, that doesn’t mean your job as the author is done. Rather, the task of marketing your book has only just begun. But the work of actually creating the book is now finished.

THE SINGLE BEST INVESTMENT IN YOUR BOOK

In an ideal world, you would invest in all of the support I outlined above. You’d have a book coach to help you map and draft your book plus at least three rounds of editing followed by proofreading.

But many authors don’t have the budget for that, so if you can only hire professional help for part of the process, which part should it be?

The most important step in writing is clarifying your ideas: nailing your central message and outlining a compelling, logical structure by which to convey it. This is the foundation upon which everything else will be built, so you want it to be rock-solid. As bestselling author Jeff Goins says, “A book can only be as deep or as interesting as the thinking behind it.” That’s why the best time to hire professional help is at the beginning in the Ideation phase.

Many first-time authors get a general concept for their book or article and dive straight into writing. But this is a huge mistake. Without a clear book map, you risk writing in circles because you’re not actually sure what you’re trying to say. You’ll waste valuable time and end up with a mess of a first draft—if you get that far. This is stage when most writers give up.

That’s why the best time to hire professional help is actually before you write your book—not after. Every bit of clarity you gain at the beginning pays off exponentially when you start writing and revising. Think about it: would you rather move a staircase after the rest of the house is built or before? How about if you need to re-do the foundation? It would be extremely costly, and at some point, it’s simply no longer possible.

Investing in a book coach will help you build that rock-solid foundation: a clear, detailed map that lays out exactly what you’re trying to say and how you’ll say it. You’ll have someone to point out pitfalls and think through possibilities, to push you to go deeper and tell you when to pull back. You’ll end up finishing a cohesive, compelling first draft in less time with less stress—one that will need far less in terms of developmental editing.

That’s what I offer in my Momentum Book Coaching package.

We start by nailing down your main idea and creating (or refining) a detailed outline—the book map—to walk you (and the reader) through the central transformation chapter by chapter.

Then I coach you through writing the first couple of chapters so that you know how to execute that outline, overcoming blocks and answering questions.

Finally, I’ll provide multiple rounds of editorial feedback on those chapters to make them as strong as possible—ready to submit as part of a book proposal should you desire.

By the end, you’ll have

→ a compelling answer to the dreaded question “What’s your book about?”

→ a powerful, logical structure and detailed outline for your entire book

→ several polished, submission-ready chapters you’re proud to send to agents, beta readers, or even publishers

You’ll grow in confidence as you clarify your voice, overcome resistance, and build the momentum you need to finish a strong first draft.

What if you already have a book map or even part of a rough draft? Great! I always customize the package for each client based on where they are in the process and what kind of support they need most.

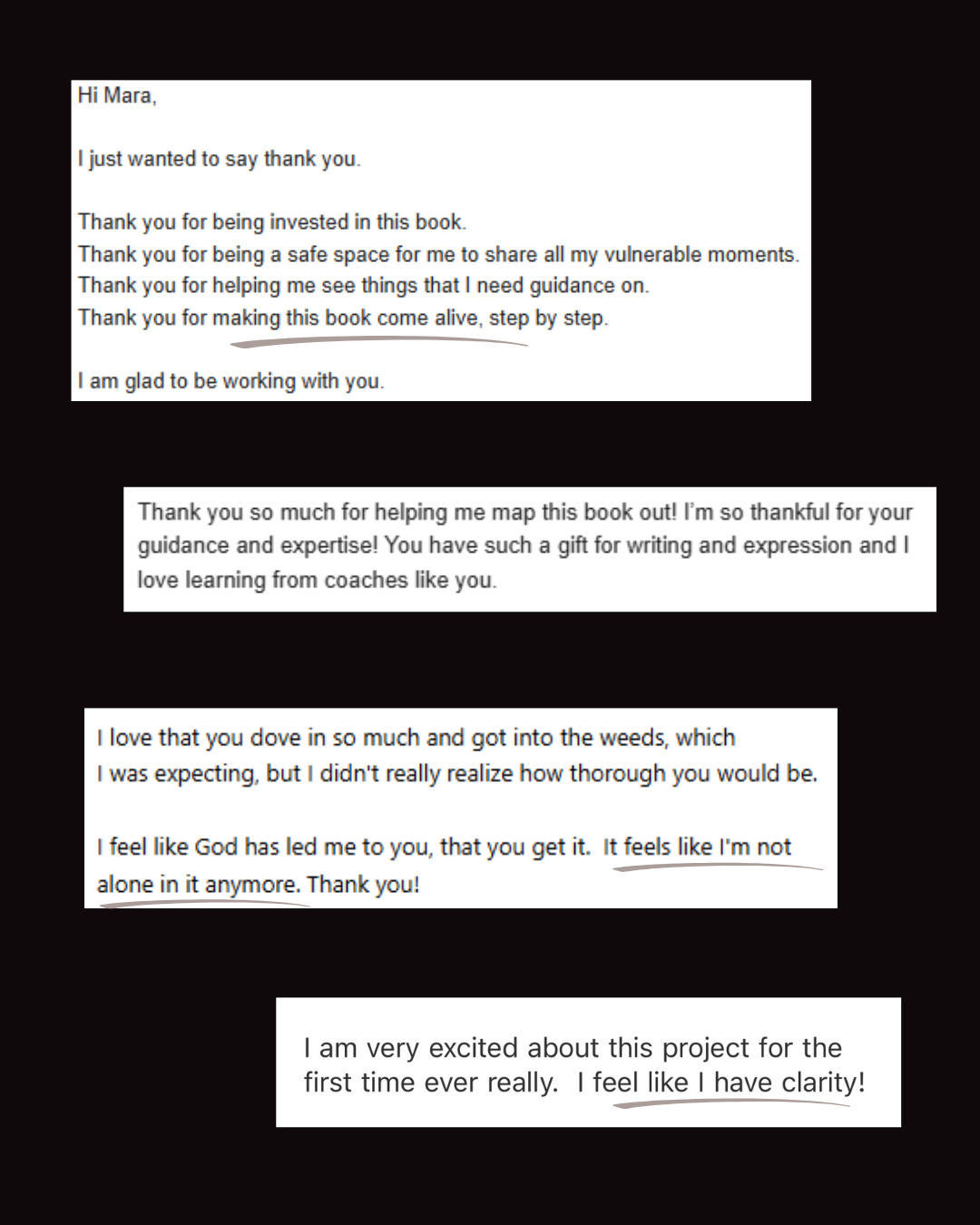

Here’s what some of my book coaching clients have had to say:

If you want to explore what it might look like to work together on your book, click here to set up a free consultation call. We’ll chat about your book idea and create a personalized 3-part plan for progress. You’ll walk away with a clearer understanding of your book’s message and the next right steps on your journey to publication.

Writing a book doesn’t have to feel overwhelming. Yes, the process is complex. Yes, the publishing world can be confusing. But you’re not meant to figure it all out alone. The more clarity and support you have from the beginning, the more likely you are to finish—and to be proud of what you’ve created.

Remember, writing a book doesn’t start with typing. It starts with thinking.

The deeper the thinking, the clearer the ideas.

The clearer the ideas, the stronger the structure.

The stronger the structure, the better the book—and the easier it is to write.

Don’t rush past those crucial first steps. Slow down, get support, and trust that the clarity you build early on will carry you all the way through.

With thoughtful planning, persistent effort, and the right guidance, you really can write a great book. And I’m here to help!

What questions do you still have about the book creation process? Drop them below, and I’ll get back to you ASAP!